Pete Alonso is one of the best bats in baseball, no question about that. But to get his bat at first base, you have to take with it his awful fielding and awful baserunning. That waters down his value to some extent. But by how much? And how does he compare to players currently on the Red Sox, and other available options?

I’ll present the data here and some other observations, so that you can compare. I’ll finish by talking about whether it makes sense for the Red Sox to add a player or stick with who they have. All the data shown here is from BaseballSavant.

The players to be compared

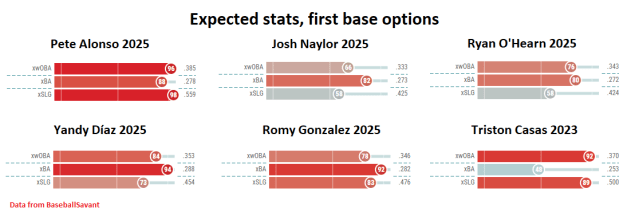

I picked the 3 first base free agents who were considered the best on the market when this offseason began, and put their stats on the top row of the comparisons below. (I started putting these together weeks ago when Josh Naylor was still a free agent.) On the bottom row I put a top first base trade possibility in Yandy Diaz, and the two top major league first base options on the Red Sox currently, Romy Gonzalez and Triston Casas.

For 5 of the players, I show their 2025 numbers. For Triston Casas, who didn’t play enough in 2024 and 2025 to give us a good idea of what he is, I show his 2023 numbers.

Expected stats

Let’s start with the expected stats. This is where they look at the velocity, launch angle and trajectory of every ball a player put in play, and tally up the probable results based on those numbers.

Focusing primarily on xwOBA, we see that all six players did well, although when you look at the actual values instead of the percentiles, Alonso is clearly separated from the pack, with only Triston Casas giving him a challenge there.

Quality of contact

Now we’ll look at quality of contact.

Alonso had the best overall contact, however Romy Gonzalez had more hard-hit balls. In fact he had the 5th highest Hard Hit% in baseball for players with over 300 PA. (Who was ahead of him? 1. Roman Anthony 2. Kyle Schwarber 3. Shohei Ohtani 4. Aaron Judge.) Yandy Diaz also hit it hard frequently.

But neither Gonzalez nor Diaz get an ideal launch angle (“LA Sweet Spot %”) as much as Alonso does. For both of them it turns out it’s because they hit too many ground balls – Diaz especially. This is likely the reason Diaz’s results aren’t as good as Alonso’s, and for Gonzalez, one of two reasons (we’ll see the other in the next section).

While O’Hearn and Naylor are limited by lower bat speed, O’Hearn improves his results by often having a good launch angle, and Naylor gets a better exit velocity by hitting on the sweet spot of the bat a lot.

Triston Casas’ 2023 comes the closest to Alonso’s 2025 among those pictured here. The differences may only be due to looking at a rookie season versus a veteran in his prime having his best season yet.

Non-contact stats

So that’s what happens when they swing and make contact. What about the numbers when they don’t make contact? Who chases pitches out of the zone too much (Chase %)? Who misses a lot when he swings (Whiff %)? Who walks too little or strikes out too much?

Alonso and O’Hearn are average in these categories. Yandy Diaz is above average, and Romy Gonzalez is well below average. Triston Casas has a great eye, but still manages to swing and miss at an above average pace. Josh Naylor doesn’t chase and doesn’t strike out, but walks an average amount.

Here we have what looks like the other reason Romy Gonzalez doesn’t get better results despite hitting the ball so hard. He chases too much. And while fixing that doesn’t necessarily fix his higher strikeout rate and low walk rate, it ought to at least help.

Fielding and Baserunning

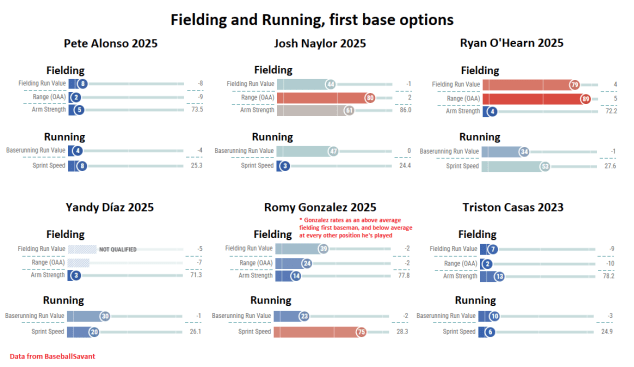

What’s left? Fielding and baserunning.

Here again we see strong similarity between Triston Casas and Pete Alonso. They’re both terribly slow, and awful at both fielding and baserunning. But being slow isn’t the excuse for the rest, because look at Josh Naylor, who is even slower, but manages to be an average baserunner and a decent fielder.

When it comes to baserunning, Romy Gonzalez is the opposite of Josh Naylor. He’s the only one in this group that could be called “fast”, yet he’s still a poor baserunner. Maybe he should get a pointer or two from his teammate Trevor Story, who runs just as fast as Gonzalez but was one of the top baserunners in the game last year. Or maybe we should give him a little credit for being an average or above average baserunner in the past.

As for good fielders, it looks like Ryan O’Hearn is the only one, with Naylor and Gonzalez a little below average. But Gonzalez split his time between first and second base (and some other spots), and when you break his fielding down by position, both in his career and in 2025, he’s been an above-average fielding first baseman, and a below-average fielder everywhere else.

Categorizing these players

So to sum up, I see two basic types of player here.

Pete Alonso and Triston Casas are the power hitters who can get on base, too, but are awful at fielding and baserunning. Yandy Diaz is, too, but with a little less power and a little better baserunning.

In the other category are Josh Naylor and Ryan O’Hearn, who have some power, but not a lot, but still manage to have above-average impact as hitters. And at everything else, they’re average, on the whole.

The 2025 version of Romy Gonzalez belongs in the O’Hearn/Naylor camp, as a well-rounded player with an above-average bat. But he has the raw tools to become much better. He’s got enough speed to become a great baserunner. He’s one of the best in the game at hitting the ball hard, but he hits it on the ground too much, and he misses it too much. And here’s the thing: the parts of his game that are lacking and that are holding him back, are all things he can learn to be better at. He can learn to be a smarter baserunner. He can learn plate discipline. He can learn to hit the ball just a little lower than he does now, to get it into the air more.

The question is, will he?

If he does, he creates a new category, combining the best of O’Hearn/Naylor with the best of Alonso/Casas, and he’d be better than all of them.

Who’s on first?

So what should the Red Sox do? If they can get Pete Alonso in to play first base for them, should they?

Alonso would certainly help the lineup. But if Triston Casas has a healthy year, he’s basically a Pete Alonso clone for much less money.

What if Casas is injured again, though? He sure seems injury prone. Then your backup plan is Romy Gonzalez, who is as good as your second-or-third best first base free agents that were on the market at the start of this offseason. And with the right coaching and effort, could end up being better than all of them in the short term.

So regardless of whether Casas can or can’t play, the Red Sox will have a plus option at first base. They don’t need Alonso to play first base for them.

But Alonso would improve them at DH. But to make that room, they’d need to trade/drop Masataka Yoshida, to whom they owe $36M over the next two years, and probably one of their 4 top-notch outfielders. Not to say they won’t; they may. But they may not.

In the end, Alonso may not add as much value as people think he will, when compared to what the Red Sox would get from the current players who he would replace. All that may not be worth the expected $150M price tag.